Conducting research to understand the role of digital nomads and Airbnb in Mexico City’s housing crisis.

Client: OPERATION GRINGO TAX

Challenge: Understand what is the role of digital nomading, expat immigration, and Airbnb in Mexico City’s housing crisis and identify viable solutions to the situation.

Written by: CHRISTIAN SCOTT, CO-FOUNDER & DIRECTOR

The role of Airbnb, expats, and digital nomads in Mexico City’s housing crisis.

Mutual Design was tasked to carry out research to better understand the key factors driving the current housing crisis in Mexico City, and identify viable solutions to the issue that could be adopted by digital nomads and expats. The project’s second phase (to come) will design and implement an analog/digital solution departing from the concept of and values of redistribution and solidary—hence the client’s project name: Operation Gringo Tax.

🔥️ TLDR: Mexico City is experiecing a crude housing crisis. There is no solution, however several actions exist that can help reduce harm and attempt to repair the situation.

The key factors we were studying were digital nomads, expat immigration, and Airbnb. We looked at how these ‘players’ were influencing the increase in housing prices, neighbourhood change, displacement and evictions, and the overall feelings and behaviours of local Mexicans towards foreigners and gentrification.

☝🏼 This project was carried out by christian scott, Co-Founder and Director of Mutual Design along with Mexican co-investigator Biaani Cantu, Master’s student at Ecuador’s FLACSO Urban Studies program, who led the qualitative component of the research between August-September 2022.

Mixed methods and and intersectional/multidisciplinary approach.

This research project required us to approach the matter with quantitative and qualitative methods—in order to understand if, how, and to what extent digital nomads, expat immigration, and Airbnb were affecting Mexico’s housing crisis. We approached the research through the disciplines of sociology, urban planning, and design-research; and with an intersectional lens taking into account class, race, and gender.

The task was a methodological challenge, since most of the quantitative data we were looking for was either not officially registered by the government, or spread throughout several government agencies and third-party databases and reports.

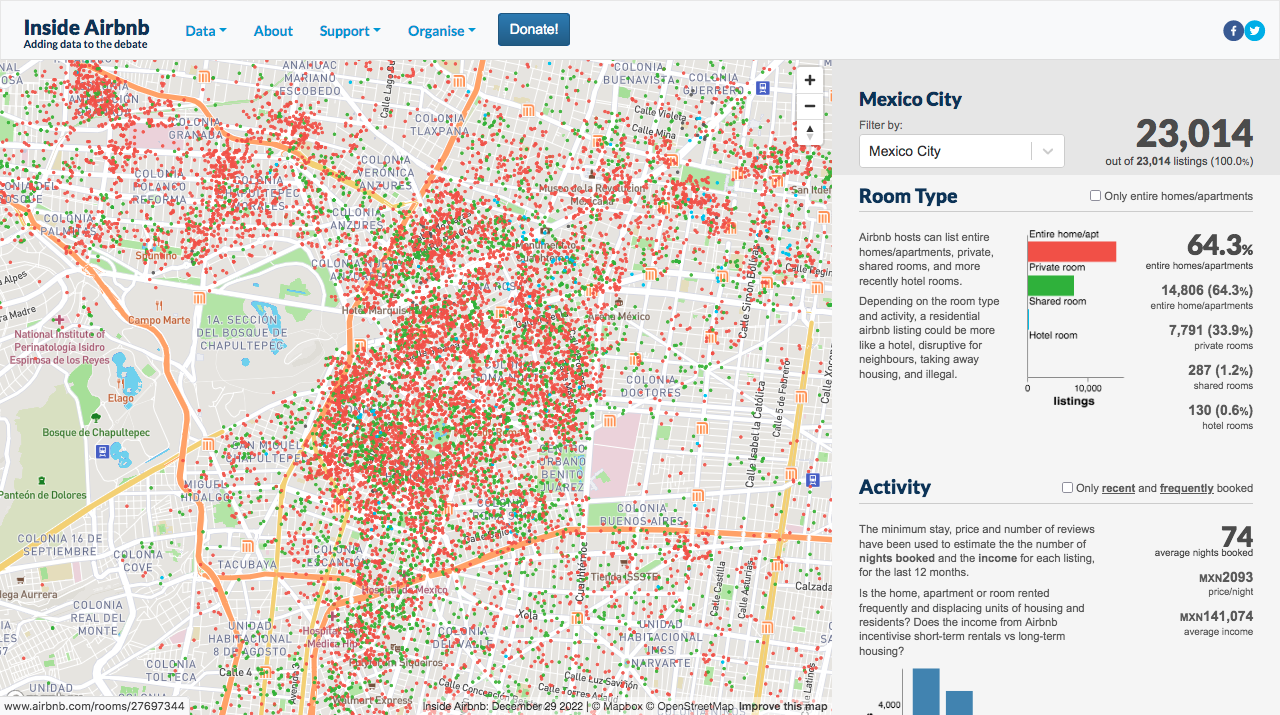

Thus, we started looking in diverse places: newspaper articles and chronicles, academic papers, government documents, and reports from think-tanks and organisations (read: Inside Airbnb is amazing).

Qualitatively, we conducted interviews and gathered stories and experiences from directly affected parties: neighbourhood associations, organized groups of displaced and evicted people, housing advocates, non-profit organizations, and University researchers.

The task was a methodological challenge, since most of the quantitative data we were looking for was either not officially registered by the government, or spread throughout several government agencies and third-party databases and reports.

Thus, we started looking in diverse places: newspaper articles and chronicles, academic papers, government documents, and reports from think-tanks and organisations (read: Inside Airbnb is amazing).

Qualitatively, we conducted interviews and gathered stories and experiences from directly affected parties: neighbourhood associations, organized groups of displaced and evicted people, housing advocates, non-profit organizations, and University researchers.

Findings: Current problematic and viable solutions.

In a nutshell the research shed some interesting findings about the problematic and the viable solutions.

The current problematic:

- The covid pandemic created a new immigration wave of expats that could now work remotely (digital nomads), and who chose Mexico City for its advantages and affordability. Mexico was 1 of 5 countries worldwide that remained open and enforced no entry restrictions during the covid pandemic.

- The rise of Airbnb reduced housing availability in Mexico City and overall increased housing prices throughout the city, particularly in the Roma, Condesa, and Centro areas.

- Mexico City’s housing crisis has been slow-cooking for decades. Other (long-term and systemic) key factors that have created the current situation are real estate speculation, the financialization of housing (housing becoming a free-market good to profit from, rather than a basic human right to be protected), and the turistification of the city (e.g., the rebranding of CDMX as a safe, desirable, and trendy international location, or the recent agreement between the City and Airbnb to make Mexico City an International Digital Nomad destination).

- A layer of symbolic non-material violence is also experienced by local Mexicans as digital nomads and expats don’t attempt to learn the Spanish language and local customs; and as the traditional uses of the barrios (neighbourhoods) are lost to quick commercial transformation tailored to expat desires, such as yoga studios, coffeeshops, coworking spaces, etc.

The viable solutions:

☝🏼 While there is no single solution to resolve the complex housing crisis in Mexico City, several actions can be adopted by digital nomads and expats to help mitigate the harm, such as:

-

Resource sharing and (financial) redistribution to local housing initiatives and organizations.

Note: Seasonal digital nomads don’t pay taxes in Mexico, however their presence increases demand in and impacts public services (which are paid by locals’ taxes).

-

Education and awareness around the issue. Yes, this involves privilege check.

- Commitment to learn the Spanish language and local customs.

-

Active support and solidarity with/towards housing initiatives.

- Commitment to not engage in harmful practices, such as running ‘Airbnb Hotels’ or actively promoting the city as an affordable magical place that other expats should move to.

Note: Seasonal digital nomads don’t pay taxes in Mexico, however their presence increases demand in and impacts public services (which are paid by locals’ taxes).

A hopeful future: the project’s next steps.

The second phase of the Operation Gringo Tax project will consist in using the data gathered to co-design with the affected parties a physical and/or digital platform or program that expats and digital nomads can adopt to actively contribute to the identified solutions.

Key numbers to understand Mexico City’s housing crisis.

Up next, a list of some key numbers the quantitative component of the research shed to better illustrate Mexico City’s housing crisis:

-

1 out of 4 households in Mexico City is rented. 51% of rentals in the city are informal—there is no written contract between landlord and tenants. [1]

-

Working class families spend +60% of their monthly income on housing. [1]

-

The 2022 ‘salario minimo’ (minimum wage) is $173 pesos per day, or $5,255 pesos per month—about $300US per month. [2]

-

Monthly income varies greatly according to educational level. For example, folks with primary education earn $4,300 pesos, high school $5,500 pesos, technical baccalaureate $6,800 pesos, professionals $11,200 pesos and post-graduates $16,000 pesos. [3]

-

In the last 20 years an estimated 400,000 families have been displaced from the (interior) city into the peripheries of Mexico City—many of those are indigenous. [4]

-

In July 2022, Mexico City had 21,669 listings. Of those, 13,083 are entire homes or apartments (60.4%), 8,077 are private rooms (37.3%), 328 are shared rooms (1.5%) and 181 are hotel rooms (0.8%). [5]

☝🏼 At the moment of writing, in May 2023, that number of listings has increased to 24,224. An 11% increase in under a year.

-

As of July 2022, 62.8% of listings were ‘multi-listings’—meaning an individual host lists either multiple rooms in the same apartment, or multiple apartments. For example, ‘Mr. W.’ has 170 listings in Airbnb, 159 of those are entire homes or apartments. As Inside Airbnb suggests, most probably the host doesn’t live there and might be violating laws (note: Mexico has no laws regulating short-term rentals). [5]

-

Unofficially, the US Embassy estimates +1.5 million US-born citizens live in Mexico. A higher number than official accounts, as many overstay their visas. This number includes some 60,000 US-born children of Mexican parents whose families have returned home. [6]

-

Due to the pandemic, migration and tourism from the US to Mexico plummeted in 2020, but has since recovered to pre-pandemic levels. 10,240,000 gringxs entered Mexico (via Air) in 2021. A 98.8% increase from 2020. [7]

☝🏼 At the moment of writing, in May 2023, that number of listings has increased to 24,224. An 11% increase in under a year.

References

[1] Azuela de la Cueva, Antonio; Emanuelli, Maria Silvia; Murillo Lopez, Sandra Carmen. Sondeo sobre la situación de las personas que residían en viviendas rentadas, hipotecadas o prestadas en la CDMX. UNAM y Habitat International Coalition Latin America. December 2021.

[2] Secretaria de Trabajo y Prevision Social. (6 January 2022). COMUNICADO CONJUNTO 001/2022. Accessed: https://www.gob.mx/stps/prensa/entra-en-vigor-incremento-al-salario-minimo-del-22?idiom=es

[3] Forbes Staff. (4 August 2021). Millennials: cuánto ganan por nivel educativo, por ciudad y por género. Forbes. Accessed: https://www.forbes.com.mx/millennials-cuanto-ganan-por-nivel-educativo-por-ciudad-y-por-genero/

[4] Cruz, A. (22 November 2021). Alto costo de suelo y vivienda, causa de expulsión de familias: Sheinbaum. La Jornada.

[5] Inside Airbnb. Mexico City. Accessed: http://insideairbnb.com/mexico-city

[6] Knobloch, Andreas (3 February 2020). Cada vez más estadounidenses se mudan a México. Deutsche Welt. Accessed: https://www.dw.com/es/cada-vez-m%C3%A1s-estadounidenses-se-mudan-a-m%C3%A9xico/a-52614792

[7] Secretaria de Gobernacion (SEGOB)—Unidad de Politica Migratoria Registro General de Personas. Boletín Mensual de Estadística Migratoria Anual. 2022, 2021, and 2020. Accessed: http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es/PoliticaMigratoria/Boletines_Estadisticos

Recommended readings

[8] Kwon, Miwon. "One place after another." Cambridge, Massachusetts and London (2002).

Photo credits: Carlos Aranda, Oscar Reygo. Screenshots taken from Inside Airbnb and CNN Business.